The Theorem of Art in Metamodernism

Seungjin Lee, organizer of DigiAna, I am often asked what kind of organization DigiAna is. I usually explain that DigiAna is an initiative that combines digital and analog elements, exploring the relationships between the digital and the non-digital (such as humans, existing forms of sociality, and living beings), and from there aims to form art communities and develop expressive practices. However, when explained this way, it is often understood simply as “the kind of digital art you see everywhere these days.” Because of this tendency, I would like here to explain—within a metamodernist context—the difference in direction between what is commonly referred to as digital art and DigiAna.

In the mainstream art world, both the creation and reception of what is called digital art are generally driven by the same motivation: the development of digital technology and the exploration of new artistic expressions made possible by it. At its core, this mindset is based on a kind of humanism aligned with capitalism—an assumption that the advancement of human sciences and technology is inherently good. I believe this function and the surrounding cultural climate are fundamentally healthy, and I hold deep respect for those involved. However, this outlook is also grounded in a modernist assumption: that the continued development of science will naturally lead to the progress of human civilization within existing capitalism.

Today, having passed through postmodernism—which emerged in the mid-20th century as a response to the modernism that spread globally from the United States in the early 20th century—we find ourselves in the 2020s, a quarter-century into the 21st century. At this point, it is increasingly evident that the formation of common sense based on either modernism or postmodernism has reached its limits. Across many fields, including art, there is a growing sense—shared not only by specialists but also by the general public—that new contemporary theorems are needed as a basis for everyday life. This tendency is particularly visible in advanced countries and throughout the internet.

What seems to be missing, however, is a comprehensive grasp of this situation and the presentation of concrete directions for moving forward. In this sense, DigiAna aims—at least within the realm of artistic expression—to present newly organized theorems for the contemporary moment with a clear sense of concreteness.

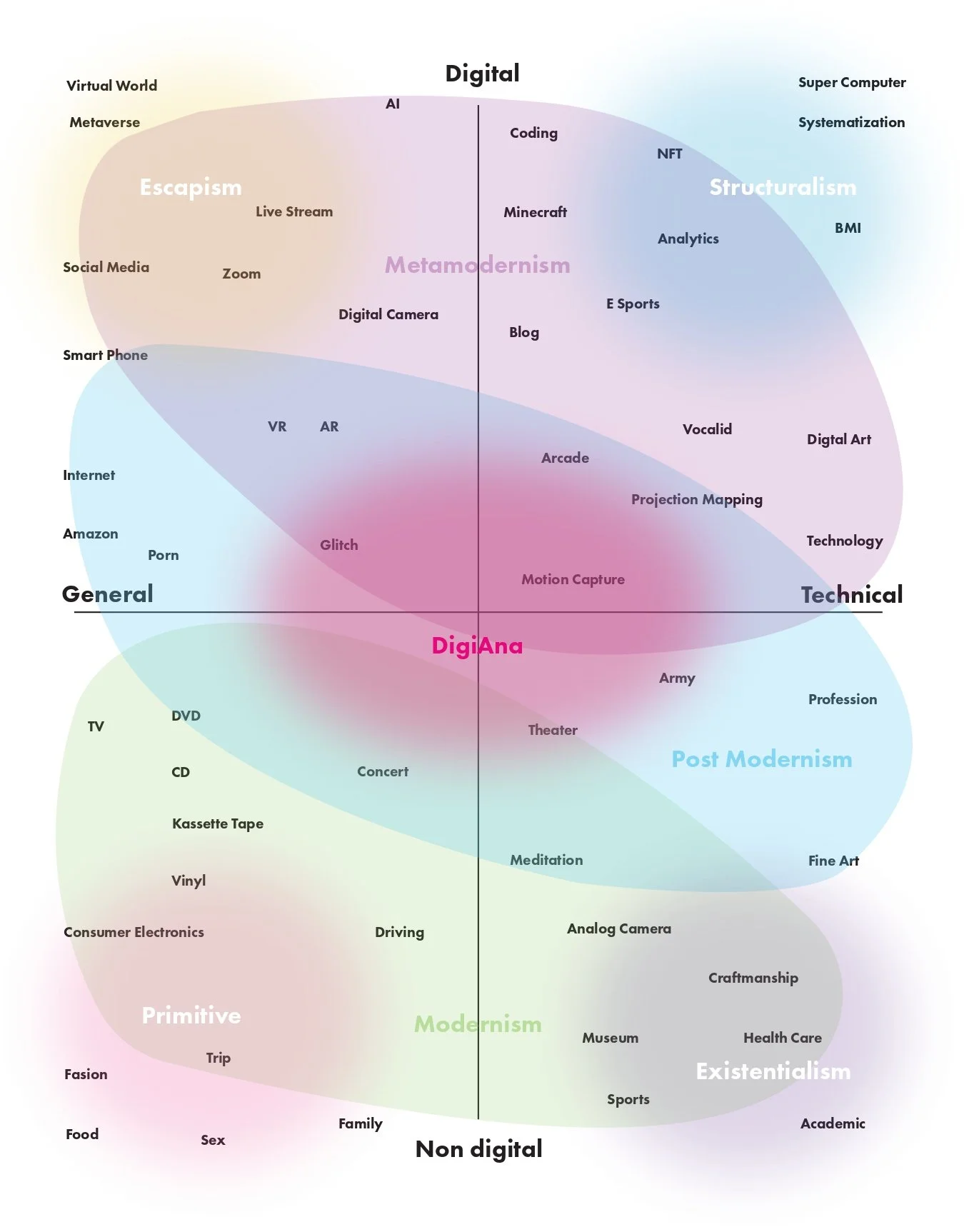

First, please look at the chart below.

The arrow at the top represents the digital; the arrow at the bottom represents the non-digital. The right side indicates specialization, while the left indicates non-specialization.

The further down and to the left one goes, the more primitive the tendency becomes—closer to earlier phases of human history. You can see the faint word “Primitive” written there. The further up and to the right one goes, the more specialization, science, and digital technology develop, and time progresses forward. Alongside humanity’s many inventions, modernism—which takes civilizational progress as its driving force—emerges, followed by postmodernism, which begins to question that progress. The point marked “DigiAna” near the center of the diagram can be seen as approaching the boundary between postmodernism and metamodernism.

So what is metamodernism? There are many interpretations, but here it is understood as a theorem that views contemporaneity from another dimension—surveying it from a meta-level perspective. Put simply, because contemporary reality is too complex to fully grasp, this approach proposes adopting an objective, receptive stance rather than a purely subjective one.

If we look toward the extreme upper-right of the diagram—where specialization and digital elements are pushed to their limits—we see supercomputers, systems of control, and structuralism. With the arrival of AI, robots, and entities that exceed human capacities, humanity is constantly generating new definitions of itself, along with hopes and anxieties. If one were to ignore all of this and simply push development further and further to the upper right, then on the opposite side—the upper left—we would see escapism: the abandonment of human qualities in favor of digitally constructed conveniences, online worlds, games, virtual reality, and immersion in fictional utopias.

The worldview of being dominated by digital technology (upper right) and the worldview of achieving new happiness through digital technology (upper left) will, under current capitalism and techno-scientific developmentalism, inevitably merge into a shared social “common sense.” The question we must ask at this stage is: is this really acceptable?

In any case, humanity has entered a phase in which new technologies force us to reconsider, almost daily, existing theorems about what it means to be human, how we understand our own existence, and how society should be structured. This is the core motivation behind DigiAna’s thinking and activities.

Let us consider this from the perspective of art.

Why do we make art? The definition of art varies by country and era, but here I will focus on the Western contemporary art world, particularly the New York art scene. Contemporary art is often said to have begun roughly 100 years ago, with figures such as Duchamp or Cézanne, or even earlier through the developments of early Impressionism. One of the most important factors in its formation was not only individual artistic activity, but also the emergence of the salon as a system. Salon culture developed in the West after the late 19th century, following revolutions for democracy that emerged from academically centered civilizational development. Prior to this, art in the West often functioned as a symbol of power, created by skilled technicians at the behest of rulers.

With the advent of democracy, art competitions emerged in which people decided what constituted good or valuable art. Within salons, artists strove to redefine existing art, propose antitheses, and construct new styles. Artists such as Monet, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne, Picasso, and Duchamp—largely active in Paris—worked within this system. After World War I, as the center of the art world shifted to the United States alongside the formation of MoMA, systems of art valuation emphasizing American art criticism, politics, and even CIA involvement came to shape artistic value.

In the 1990s, postmodernism arose to question these systems, along with new evaluative axes from kitsch and street art. Still, art evaluation largely remained rooted in an American-centric perspective. In the 21st century, with the development of digital technology and internet culture, and with a growing emphasis on diversity over American centralism, major art fairs in recent years have tended to provisionally valorize art from Asia, Africa, lesser-known countries or tribes, as well as NFTs and digital art. However, the kind of “spark” that once emerged from redefining or opposing Western- and American-centered art contexts—the sense of novelty and excitement as art—has become increasingly rare.

This is because the very context built on Western humanism and techno-progressivism has itself lost its former rigidity. Without fixed standards, it is difficult for strong reactions, oppositions, or genuinely new ideas to emerge.

For example, one phenomenon of contemporary society brought about by technological convenience is the declining birth rate in advanced countries. Stress and anxiety from intense competition, reduced opportunities for forming direct communities, shifts in motivation toward romance, sex, and childbirth, and broader questions about overpopulation, environmental destruction, and the limits of Earth’s resources—all of these are now widely encountered by ordinary people through online information. As a result, many are forced into daily self-questioning: Why do we exist? Why do we work? What does it mean to be human? Unless we frame this as a positive trial in human evolution—organizing problems daily and cultivating a mindset aimed at solving them—modern life easily accumulates anxiety and dissatisfaction, leading to self-loathing, depression, and other contemporary illnesses.

In art-making as well, as AI automatically generates paintings, sculptures, videos, games, and music in ever-increasing quantities, artists are inevitably forced to redefine what art itself means.

Rebuilding ideology through a return to American or Western centralism, or nation-building under fascistic policies like those associated with Trump, does not genuinely motivate people who share a democratic, online-civilization mindset—that all people in the world share common human rights.

So what should we do?

DigiAna proposes the following: first, it is crucial to calmly understand that this is the kind of era we are living in. Through artistic practice and community-building, we want to communicate this understanding to society.

DigiAna also seeks not only salon-centered systems of evaluation, but ways of integrating smoothly into the formation of new social understandings of humanity. Whether DigiAna’s activities are evaluated by capital or art systems and converted into money or authority is secondary. Alternatively, we may choose to set that aside and focus on building new, healthy communities through art, centered in New York—a uniquely branded region that still symbolizes capitalism.

As the organizer writing this text, I, Seungjin, genuinely and vividly believe in this philosophy and its significance, with a sense of future excitement. I see this as a challenge and an adventure for a new kind of humanity—and even as the beginning of a new chapter in cosmic history.

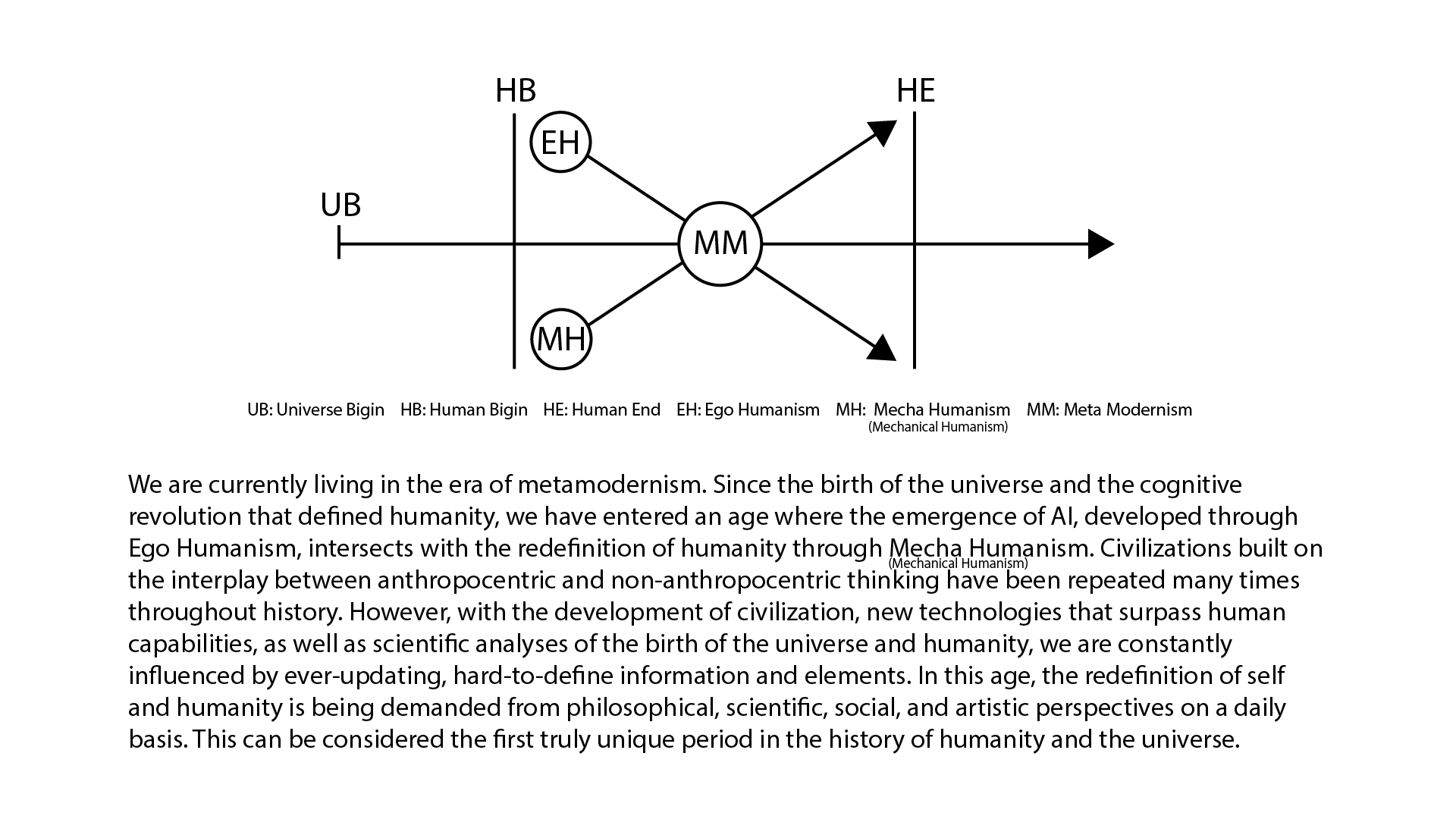

Please look again at the diagram below. As noted in the accompanying text, from here on we might move beyond ego-humanism—society built purely from a human-centered perspective—and instead incorporate mechahumanism: viewing humans and ourselves through a meta-level lens grounded in the physics of the universe, and approaching daily life and artistic practice as part of an unfolding cosmic history.